Journey and Arrival

“Transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of civilization and he will grow to possess a civilized language and habit.”

-Richard H. Pratt

Pratt’s Experiment in Education

Military officer Richard Henry Pratt devised an approach to Indian assimilation while overseeing Indian prisoners at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. The prisoners’ hair was cut and they were dressed in military uniforms. Pratt established classrooms where the prisoners learned English. Prisoners were sent to work for local individuals and businesses in the community in a practice called the Outing Program, which was used later in the Indian schools.

In 1878 Pratt took 17 of the youngest released prisoners to Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, a historically black university. He lobbied to set up his own school for Indian students and found a location at the abandoned military barracks at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, now the site of the U.S. Army War College. Carlisle Indian Industrial School was in operation from 1879 to 1918.

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him and save the man.”

-Richard H. Pratt, 1892

In some ways Pratt was progressive for his time, believing that all individuals could advance to the same level of learning, given the proper environment and education. The prevalent racist view of the late 1800s was that people of color were inferior in intellectual and physical abilities.

-Angel De Cora, student at Hampton (1883-1888) and went on to teach at Carlisle Indian School (1906-1915)

The Trauma of Separation

“I still picture my folks to this day, just standing there crying, and I was missing them. I got on the train and I don’t even know who was in the train because my mind was so full of unhappiness and sadness…”

-Juanita Cruz Blue Spruce, Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, attended Santa Fe Indian School, 1915

“I remember it was in October they came to get me. My mother started to cry, ‘Her? She’s just a little girl! You can’t take her.’ My mother put her best shawl on me.”

-Juanita Cruz Blue Spruce, Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, Santa Fe Indian School student, 1915

“In my decision to go [East to Carlisle], I gave up many things dear to the heart of a little Indian boy, and one of the things over which my child mind grieved was the thought of saying goodbye to my pony. I rode him as far as I could on the journey, which was to the Missouri River, where we took the boat. There we parted from our parents, and it was a heart-breaking scene, women and children weeping. Some of the children changed their minds and were unable to go on the boat, but for many who did go it was a final parting.”

-Luther Standing Bear (Oglala Lakota) reflecting on his journey to Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Pennsylvania, in his memoir Land of the Spotted Eagle, 1879

“I was recruited as a teenager. . .I was the first one in my family to go. I was kind of a black sheep. My mother really objected to my going to school; she did not want to release any of her children for school. My uncle and other relatives tried to persuade her. . .The day that the recruiting police came to Round Rock, she gave in and let me go. My brothers and sisters did not come; I was the only one.

-Frank Mitchell, Navajo, sent to the U.S. Government School in Fort Defiance, c. 1895

The Process of Civilizing. “Erase and Replace.”

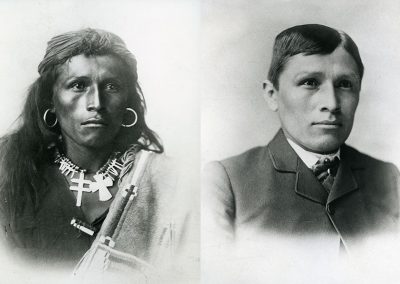

“The next day the torture began. The first thing they did was cut our hair … while we were bathing our breechclouts were taken, and we were ordered to put on trousers. We’d lost our hair and we’d lost our clothes; with the two we’d lost our identity as Indians.”

-Asa Daklugie (Chiricahua Apache), 1886, taken from Fort Marion to Carlisle Industrial Indian School

Very shortly after children arrived at the boarding schools, the process of stripping away their Native identity began. Students endured haircuts, delousing (whether needed or not) and bathing in lye soap. Home clothing and moccasins were removed and discarded, replaced by military uniforms and Victorian dresses and lace-up shoes.

“When you first started attending school, they looked at you, guessed how old you were, set your birthday, and gave you an age. Then they’d assign you a Christian name. Mine turned out to be Fred.”

-Fred Kabotie (Hopi), attended Santa Fe Indian School 1915-1920

Students were given a number and an “American” name. Student records documented their height, weight and lung capacity—a screening for tuberculosis. Administrators were reluctant to accept sick children. Deaths of students tarnished the school’s reputation. New students were forbidden to speak their Native language, and they struggled to communicate without being punished.

Children’s spiritual lives were interrupted by their removal from their tribal surroundings. At the boarding schools they did not experience puberty ceremonies which marked a young girl’s transition to womanhood, or a young boy’s passage into being a man. Instead puberty was treated as something one did not discuss or celebrate, a direct contradiction to many tribal ceremonies.

“When they first took us in school, they gave us government lace-up shoes, and they gave us maybe a couple pair of black stockings, and long underwear, about a couple of them, and… slips and dress. Then they gave us a number. My number was always twenty-three.”

–Lilly Quoetone, Nahwooksy, Fort Sill Indian School Experience, 1981 (publication date)

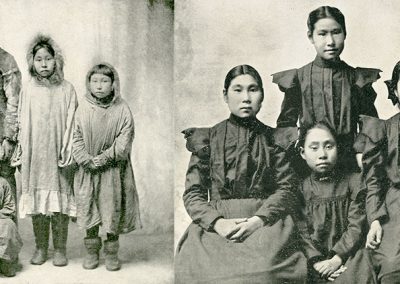

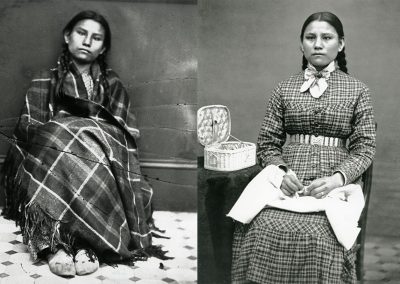

“Before and After”

Eskimo group before and after they entered Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 1897. J.N. Choate, photographer. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Portrait of Annie Dawson, Carrie Anderson and Sarah Walker, upon their arrival and 14 months after at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, 1878. Hampton University Archives, Hampton, Virginia. RC125(7)2.1.7.1

Portrait of Zie-wie Davis (Sioux, Crow Creek Agency), 1878, one of the first to arrive at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, and 4 months later. William Larrabee, photographer. Hampton University Archives, Hampton, Virginia. RC125(7)2.1.7.3 and RC125(7)2.1.7.4

Resistance

In 1894, the Hopi people resisted the U.S. government on several counts. They refused to send their children to the government boarding school in Keams Canyon. The school was in dismal condition—overcrowded and inadequately furnished—and Hopi leaders opposed the assimilation program. U.S. cavalry troops arrived in the Hopi village of Oraibi and arrested 19 leaders for refusing to send their children to school. They were taken to Fort Defiance, put on a train and shipped to Alcatraz, in San Francisco Bay. They were incarcerated for nine months, missing important ceremonies at home such as the planting and harvesting seasons.

This was one of the more overt acts of resistance to the schools, but families took many measures to keep their children at home.