Health

“There is something fundamental here. We cannot solve the Indian problem without Indians. We cannot educate their children unless they are kept alive.”

-Cato Sells, responding to the serious mortality rate at U.S. Indian Schools, in Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1916

Health conditions at Indian schools in the late 1800s and early 1900s were deadly. Overcrowding, poor diet and unsanitary conditions resulted in physical and emotional trauma, all factors that contributed to diseases and early deaths for many children. In the late 1800s, communicable disease, particularly tuberculosis and influenza—became a problem at the boarding schools. Hundreds of Indian students fell victim to deadly diseases that were propagated within the schools’ close confines.

Many of the off-reservation boarding schools built hospitals, but government officials and health care providers did not comprehend the contagious nature of tuberculosis, and they failed to separate sick children from the rest of the student body.

With high mortality rates, almost every school had its own graveyard. Common killers included tuberculosis, influenza, whooping cough, measles and smallpox. In 1915 the Indian tuberculosis incidence rate at Indian boarding schools (and on reservations) was four or more times the non-Indian rate. Three out of 10 students had trachoma, a contagious eye infection. Indian rates of measles, chickenpox, mumps, smallpox and other contagious diseases were double or triple the national rates.

“Of all the changes we were forced to make, that of diet was doubtless the most injurious, for it was immediate and drastic. White bread we had for the first meal and thereafter, as well as coffee and sugar. Had we been allowed our own simple diet of meat, either boiled with soup or dried, and fruit, with perhaps a few vegetables, we should have thrived. But the change in clothing, housing, food and confinement combined with lonesomeness was too much, and in three years nearly one half of the children from the Plains were dead and through with earthly schools. In the graveyard at Carlisle most of the graves are those of little ones.”

-Luther Standing Bear, Oglala Lakota; attended Carlisle Indian School 1879 (age 11) to 1885.

Carlisle Indian School Hospital, c. 1907. A.A. Line, photographer. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

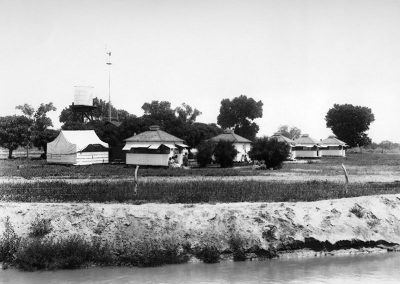

Tuberculosis quarantine huts, 1908, at northwest corner of 16th Street and Indian School. RC125(6)3.6

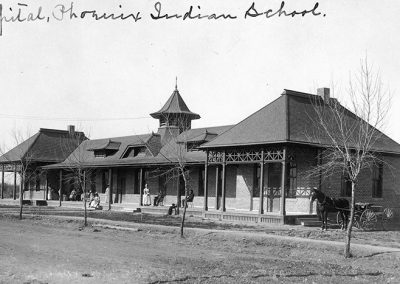

Phoenix Indian School Hospital, c. 1896. Arizona Historical Foundation, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona. RC125(7)2.1.12.1

“My Dear Father—I have been sick but now I am very well, so I am very glad I was going to write to you a few lines. And then I ask you something. I want to know my mother. She sick yet or better. Dear father I want to know how are you and my relations.”

-Luther Standing Bear, letter home, published in the Carlisle Indian School newspaper Eadle Keatah Toh, vol. 1 no. 12, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, July 1881

“My Dear Father, American Horse: I want to tell you something, and it makes me feel very glad. You tell me that my brother is married and that makes me feel very glad. My cousins, and brothers and I are all very well at this Carlisle school. We would like to see you again. I am always happy here, but lately I sometimes feel bad, because you tell me that my grandfather is getting very old. . .Tell [me] if my grandfather is well. If he gets sick, tell me.”

-Maggie Stands Looking, one of first students at Carlisle Indian School, 1881

“Your son died quietly, without suffering, like a man. We have dressed him in his good clothes and tomorrow we will bury him the way the white people do.”

-Richard H. Pratt, founder of Carlisle Indian School

-Lawrence Webster (Suquamish) student at Tulalip Indian School, 1908

Homesickness and Running Away

The deliberate separation of children from families, communities and familiar surroundings was a central part of the boarding school experience. This early boarding school period created great unhappiness among the students and their families. The trauma of being separated from family and community drove many students to run away. Some attempted to walk home, others tried to catch a ride on a train.

Running away was common, and the risk of dying of exposure a reality. Running away was so common that residents who lived near a federal school were offered a reward if they captured and returned fugitive students. Chilocco Indian School (Oklahoma) had a standing agreement with the local police department: a “bounty” ($1.50 to $5.00) per captured runaway student. In 1900, Phoenix Indian School housed more than 700 students. Ten to 20 students ran away each month and a corps of men was assigned to apprehend and return truants.

“Dear dad, I suppose you will be surprised to know that I am here. I know I have made a big mistake and it is hard for me to think of the grief it will cause you Dad. Dad I was discouraged I just went mad. I realize what I have done and am very sorry. I’ll go back next year and like it.”

-Flandreau Indian School (South Dakota) runaway, 1931