–Thomas Jefferson, 1803

Introduction

Indigenous Education

“For Indigenous people, our education didn’t begin with government institutions. Our education didn’t begin with Christian missionaries or Christian schools. Native people have some of the longest, the oldest forms of education in the Americas, and throughout history Native people have drawn upon that history and used it to enlighten the world, and used it to help them understand the situations they find themselves in, and they used it so that they can look ahead toward the future.”

-Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, interview, August 23, 2017

Like all human communities, Indigenous people of North America have a long history of educating their young people. Cultural learning teaches individuals who they are, who their people are, and how they relate to other peoples and the physical world around them. Knowledge is transmitted through oral histories. Individuals learn the origin of their community, rules of behavior and the purpose of existence of individuals, their community and their world. The three Ls in indigenous education are Listening, Looking and Learning. From a young age, children are taught to listen carefully to their elders as they are told stories of their ancestors and creation. Essential observational skills are practiced. Youth are equipped with the skills and knowledge necessary to sustain community life.

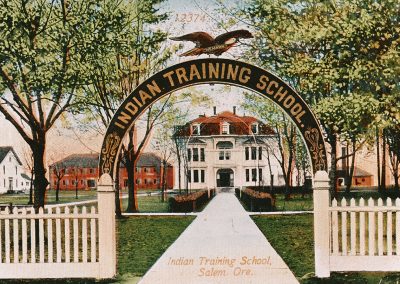

Why Boarding Schools? ‘Americanizing’ American Indians

The Indian boarding school system in the early 1800s began under the auspices of the Department of War. The Indian Wars—the various armed conflicts between U.S. settlers and Native Americans from earliest contacts, mostly land disputes—resulted in a legacy of poverty and disease as Native people were relocated and confined to reservations. The “Indian problem” was a topic of national debate. The founder of the Indian Rights Association, Herbert Welsh, stated in 1886 that his Christian reform movement wanted to deliver the Indian “from the night of barbarism into the fair dawn of Christian civilization.”

Resolution of the problem was believed at the time to require eradication of Indian cultures. Education was seen as the tool to “civilize” the “savages.” The federal policy of forced assimilation was a war waged on children.

As the Indian Wars were winding down, government officials found it was less expensive to educate Native Americans than to fight wars. Carl Schurz, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, estimated in 1881 that it cost nearly a million dollars to kill an Indian in warfare, while it cost only $1,200 to enroll an Indian child for eight years of schooling.

Off-reservation American Indian boarding schools were established in the late 1800s and early 1900s to remove Native youth from their families and communities and force them to learn the English language and to accept an American lifeway and Christianity. The policy of cultural annihilation continued for decades.

Manifest Destiny, Removal, Relocation and Displacement

In the 19th century, extreme changes were imposed on Indigenous peoples in the United States. As settlers claimed more land, tribes were forcibly confined to smaller and smaller areas. Federal and state governments removed American Indians from traditional lands and restrained their political power.

The doctrine of manifest destiny—the philosophy that drove 19th century territorial expansion by Euro-Americans, expanding dominion while spreading capitalism and Christianity—justified settler claims to Indian lands, pushing tribes off their homelands and onto reservations.

Paternalistic Indian policy in the 19th century proposed to bring “civilization” to Native Americans. The philosophical context at the time was based on the theory of social evolution, the belief that societies evolved from a state of barbarism to civilization.

The primary concern in all Indian education policy was to make the Indian self-supporting—not only for the benefit of the individual, but also to end governmental support of Indians whose means of subsistence had been destroyed.

“It is cheaper to give them education than to fight them.” —Hiram Price, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1885

Who Benefited From American Indian Boarding Schools?

The combination of allotment—breaking up tribal reservation lands for individual ownership—and the removal of young people to distant boarding schools devastated Native family and community networks. The ongoing dispossession of American Indian land allowed settlers to colonize the “surplus” lands.

American Indian boarding schools were desirable institutions in mainstream communities, fueling local economies with new jobs in construction, teaching and administration, food service and transportation. Boarding school students provided inexpensive labor for menial jobs. As schools developed “Outing Programs,” students were sent to local families for a summer or longer to work as domestic laborers or agricultural hands, or in businesses.

Student labor was necessary to maintain the schools. Many of the federally operated off-reservation schools, such as Phoenix Indian School, Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, Genoa Indian Industrial School and Stewart Indian School, used student labor to build campus buildings, farm the land to feed the students, raise stock to produce eggs and milk—all the self-sustaining operations of cleaning, laundry, carpentry and cooking. Without student labor, the schools would have been too costly to operate.

Who Attended Boarding Schools?

Prisoners and hostages were among the earliest students at American Indian boarding schools. After release from Fort Marion prison in 1878, 17 young captives were taken to Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute and then to Carlisle. In 1886, Chiricahua Apache child prisoners of war were also taken to Carlisle.

Many children were forcibly removed from their homes by uniformed Indian police. Families were coerced or children kidnapped and taken to American Indian boarding schools to maintain student enrollment numbers. Sometimes families had to decide which child to send from the family. In his memoirs, Fred Mitchell admits he was picked because he was the “black sheep” in his family. In 1917 the Indian Bureau issued a notice, “The Rules for Sending Children to Schools,” which banned the strategies used in earlier years. Recruitment and forced enrollment continued, however, through later decades.

Not all the children in a family were enrolled in boarding schools. Some stayed at home to help work the fields or support an elder. The breakup of the family was difficult for everyone.

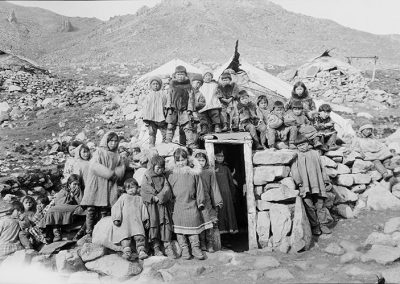

Siberian Eskimo dwelling and children. C.W. Scarborough Photographic Collection, UAF-1988-130-34. Archives, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska.

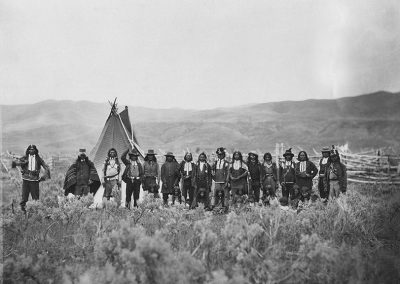

Shoshone Indians, n.d. Andrew J. Russell, photographer. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven, Connecticut.

A Word About Words

When possible, we refer to a tribal nation by the name its members use. When speaking in general terms, we use “Indigenous,” “Native” and “Native American.” “American Indian/Alaska Native” is used as well to refer to Indigenous people of the United States. Indigenous or aboriginal people of Canada are referred as “First Nations,” “Inuit” or “Métis.” We use the terms American Indian “boarding schools” and “residential schools” interchangeably in the U.S., whereas Canada, Australia and New Zealand use “residential schools.”

Some of the content inAway From Home: American Indian Boarding School Stories is disturbing. We use quotations and language from the 19th century philosophical and ideological perspective to describe the historical context of policies of that time (for example, using terms such as “savages” and “barbarian” and the need to “civilize”).